What happened in and through Turkey’s Central Bank will not stay there

No reserves era will be over, but right now, it presents hard choices for both Erdogan and the opposition (#4)

Due to the deadlines and applications I juggle, I am posting the final piece of mini Turkey’s Central Bank series three days later than I planned.

In the first entry, I summarized how and when the CB lost its reserves and how it can act as if nothing happened. In the second one, I focused on the turning points in 2020-21 and suggested that the CB was slightly paralyzed, waiting for the new economic orientation to produce fruitful results.

It is time to briefly discuss the Erdogan administration’s choices and the opposition’s economic promise.

Full Monty

Turkey’s Central Bank lost its operational autonomy around 2014, around the partial suspension of the constitution (I refer to the events before the conflicts and massacres of 2015 or the state of emergency of 2016-18. Erdogan kept his position as a party leader for a few weeks after the first presidential election in 2014 and then continued acting as a party leader, which was unconstitutional at that time). In the late 2010s, the state not only sponsored various credit expansion campaigns but also intervened more frequently in the foreign exchange markets.

Central Bank’s loss of reserves in 2018-19 reflected the desire to mitigate currency depreciation. However, in 2020 the quasi-fix the monetary authorities performed necessitated several rounds of FX sales. They were those sales the opposition referred to in a successful political campaign in 2021, with the slogan, “where is the USD128 billion?” (referring to the estimated loss of CB reserves in recent years).

To derive an opportunity from the crisis and satisfy the new and would-be exporters, the Erdogan administration sought to re-brand the export orientation as the New Economic Model in 2021 (the first use was in 2020, and similar tropes can be traced back to late 2018, below is the link of one of the press meetings that frames the beginning as December 2021).

The pillar of this model is to maintain depreciated Turkish lira and minimize the current account deficit. The decision was a new shockwave to the residents and corporations in late 2021. Fearing that the lower policy rates (key interest rate of CB – the weekly repo interest rate) would trigger a currency crisis, households and corporations’ dollar rush resulted in a new currency crisis in a performative way.

The foreign exchange-protected lira deposit scheme was introduced in late December 2021 to reverse the currency collapse. It lets commercial banks offer 300 basis points more than the policy rate of CB to deposit holders. To give an example of the burden of the Treasury and Central Bank, let’s take the example of a protected deposit with a maturity of 3 months. Even if the lira depreciates against hard foreign currencies by more than 4.25 percent (more or less) in 3 months, the lira deposit holder will not feel the pain since the state funds will close the gap. It is similar to a naked option since the Treasury and the Central Bank do not hold a corresponding position in the option’s underlying, i.e. USD or hard currencies.

It calmed down the FX market in Turkey but further cornered the CB. Turkish state paid 11.7 billion lira to deposit holders in the first three months, and the total fiscal burden will be massive. Tax exemptions for corporations which shifted their funds to lira are as much as the actual payments for the first group of deposit holders (who opened their accounts in late December 2021).

The Treasury and the Central Bank can maintain the scheme until the 2023 plebiscite (I use the term deliberately). After that, the Erdoğan administration, if the authoritarian strongman wins the plebiscite, will face the problem of ending this protection. It might lead to a new dollar rush. Still, it is too expensive to maintain this shelter for extended periods.

The high inflation rate is partly an outcome of the currency crises, and it now ensures that the depreciation of the lira will continue in 2022 (the official inflation figure is 70 percent annually in April 2022, while the CB policy rate is still 14 percent and the FX-protected lira deposit interest rate is 17 percent).

Is orthodoxy the answer?

With its various stripes, the liberal and centrist opposition (symbolized by six parties collaborating to promote an orderly transition to a parliamentary system starting in 2023) promise to restore CB autonomy. It complements the economic program that strives to lure foreign investors and boost confidence in the Turkish economy.

Though the link is not visible, it will end up in a mainly orthodox economic and regulatory framework, in which the state, as the ultimate guarantor, has to act rapidly. Within this framework, the economic policy should boost the FX earning industries in a few months and make the lira-denominated financial securities attractive to the international financial capital.

The practical complementary step in this approach is to drastically increase the CB policy rate with the outcome of condemning the economy to a recession for a few quarters. In other words, unless the global financial circumstances change drastically in mid-2023, it will not be possible to accumulate FX reserves quickly. And only under loose global financial circumstances the new administration can avoid a recession.

This is the hard choice of liberal/centrist opposition. Since Turkey’s economic performance is heavily dependent on financial inflows, the CB might have to maintain a tight monetary policy for not just a couple of months but a couple of years.

In a country suffering from double-figure unemployment and ready to implode because of deep socioeconomic inequalities, pushing the economy into recession and implementing tight monetary policy for several years is equal to creating a dystopian environment. The Erdogan administration knows it well and insists on state-sponsored credit campaigns. That is not the case for orthodox minds, and it creates an additional disadvantage for the opposition. (e.g. as of writing this piece, Erdogan declared that they would launch a new campaign to boost house sales and support the construction sector. Even though such a campaign skyrockets house prices, an alive and kicking construction sector is vital for Erdogan before the elections).

Waiting for Godot

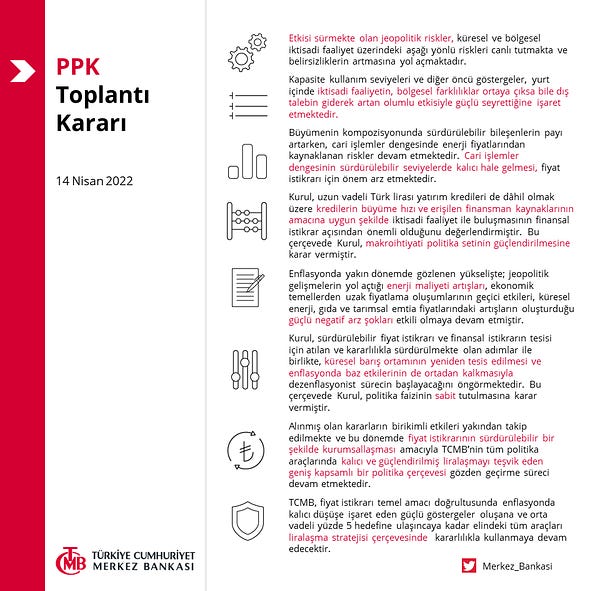

As I mentioned half-jokingly, the paralyzed CB in Turkey waits for global peace (the monetary policy council repeated the same line in the April meeting) and continues to update their official expectations under the highest inflation rates of the last 20 years.

The CB experts and the country’s money managers watched the creation of a cul-de-sac in 2018-19. The no reserves choice helped the Erdogan administration postpone some economic problems and avoided a more severe crisis in 2020-21. But it seems to have paved the ground for a nightmare that entraps the minds of policymakers in 2022 and for months to come.

Turkey’s CB still has over USD50 billion liabilities on the off-balance-sheet. No one exactly knows how this picture can be reversed without policies that will dramatically impact the everyday lives of millions.

The end of the no reserves era is not that far away, and it will be nasty.